Images

- The Programma 101 (Courtesy of www.storiaolivetti.it – Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti)

- Side-view of the Programma 101 (Courtesy of www.storiaolivetti.it – Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti)

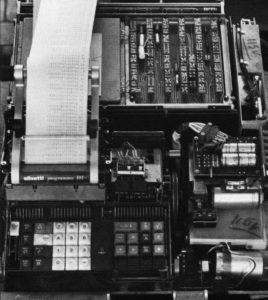

- Top down picture of the Programma 101 (Courtesy of www.storiaolivetti.it – Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti)

- Prototype of Programma 101 (Courtesy of www.storiaolivetti.it – Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti)

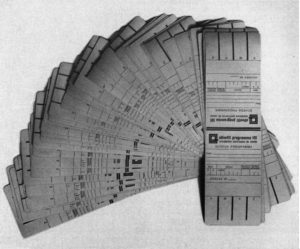

- Magnetic cards for programs storage (Courtesy of www.storiaolivetti.it – Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti)

- A Production line assembling Programmas 101 (Courtesy of www.storiaolivetti.it – Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti)

- The Programma 101 at the BEMA (Courtesy of www.storiaolivetti.it – Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti)

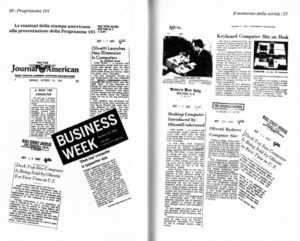

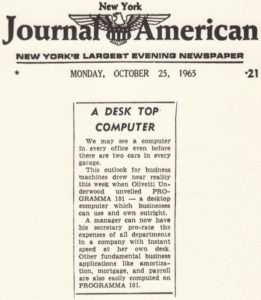

- Selection of newspaper articles reporting on the Programma’s success at the BEMA (Courtesy of www.storiaolivetti.it – Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti)

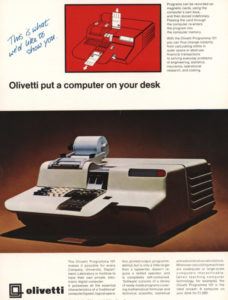

- A Programma 101 ad (Courtesy of www.storiaolivetti.it – Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti)

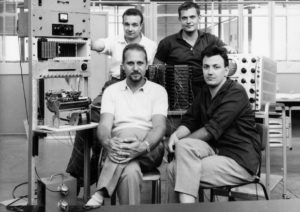

- The Perotto Team. First Row from left: Piergiorgio Perotto, Giovanni De Sandre. Second row from left: Gastone Garziera, Giancarlo Toppi

- The old Olivetti Electronics Division. Mario Tchou is in the first row, fourth person from the left, while Piergiorgio Perotto is in the third row, third person from the left (Courtesy of www.storiaolivetti.it – Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti)

- The inner components of the Programma 101 (Courtesy of www.storiaolivetti.it – Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti)

- A NASA scientist doing some maths on the Programma 101 (Courtesy of www.storiaolivetti.it – Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti)

- NASA scientists using the Programmas 101 (Courtesy of www.storiaolivetti.it – Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti)

- The Programma 101 at work in an operating room (Courtesy of www.storiaolivetti.it – Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti)

- A small piece about the Programma 101

Video

Suggested Readings

- Paul E. Ceruzzi, A History of Modern Computing, The MIT Press

- Paul E. Ceruzzi, Computing – A Concise History, The MIT Press

- Giovanni De Sandre, Microstoria del Progetto del Programma 101

- Luciano Gallino, La scomparsa dell’Italia industriale, Einaudi

- Piergiorgio Perotto, P101: quando l’Italia inventò il personal computer, Edizioni di Comunità

- Marco Pivato, Il miracolo scippato, Donzelli

- Lorenzo Soria, Informatica: un’occasione perduta, Einaudi

Suggested Sites

- Laboratorio Museo Tecnologicamente

- Fondazione Adriano Olivetti

- The CIA spied on Adriano Olivetti for ten years – TG2

Music Credits

- Main Theme – Valerio Mirone

- Parallel Stories – Bisou de l’enfant sauvage

- Lying Here Helpless – Daniel Birch

- Decompress – Lee Rosevere

- Blue Lobster – Daniel Birch

- Systematic – Lee Rosevere

- Building Tension – eddy

- Defeat – BoxCat Games

- Gordo José – Milton Arias

- Run in the Night – The Good Ladwz

- Poupee Valsante (Waltzing Doll) – Maude Powell

- Scale Free – Oorlab

- Unanswered Questions – Kevin MacLeod

- Garage – Monplaisir

- Serial Killer – John Bartmann

Transcription

What you’re hearing now, is the voice of the future. It’s a clunky, mechanical sound and no one would ever consider it to be the language of tomorrow. But due to this bunch of thumps and clonks, you’re able to hear my voice now, because if they never had resonated you wouldn’t have a smartphone in your pocket or a laptop at hand, you wouldn’t be listening to this podcast or to any podcast ever. You see, these weird noises are where it all began, where computer science made his first big leap forward. You’re listening to the breath of the first personal computer ever created, the ancestor of many machines that populate our world. Its name is Programma One-oh-one.

Twelve years before Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs laid hands on the Apple One, the Programma One-oh-one was already clicking and whirring around the world. It is the fruit of Italian ingenuity, otherwise, we wouldn’t be talking about that, but it’s also something else. If you listen closely, among the taps and the thuds, it’s telling us a different story. This story talks about a group of men who fought, who overcome adversities, led by a few, strong beliefs. They thought that anyone should have access to computers in a world where only a few could. They believed that machines should adapt to the man’s wishes, and not the other way around, like everyone else thought back then. They hoped to see a world where computers helped children to do their homework while the only computers around were gargantuan mainframe calculating how missiles could annihilate the next town before the enemy could strike back. This is the story of a group of men who, in the sixties, imagined our world, the present world, their world of the future. And it wasn’t easy, you know. Many called them fools: top managers made their life difficult at work. Leading entrepreneurs of the time deemed them to be jokers, only good at wasting money. Analysts claimed that their project was unfeasible, their dream was out of reach. But they were wrong, they were all wrong in the end. I’ll show you why and how. Now bear with me, this story comes from Ars Dicendi and today we’re dealing with Italian Culture.

Perhaps you have already heard something about the Olivetti company, based in Ivrea, Piedmont, Italy. Until the seventies, Olivetti had been a historical manufacturer of typewriters and mechanical calculators. Their machines were renowned all around the world for being beautifully designed, from the shape of the space bar, to the color scheme of the chassis. They were pretty, they worked well and they sold better. Several historians tried to decipher why Olivetti fared this well in the fifties and came out with several hypotheses. All of them took into account the role of Adriano Olivetti, the leader of the company whose ideas were way ahead of his time. He took the reins of the family company in 1938, just after the war ended. In the early fifties, he started developing a keen interest in electronics. According to Beniamo de’ Liguori – secretary-general of the Adriano Olivetti Foundation – the curiosity Adriano showed about electronics was at least twofold.

“On one hand, Adriano Olivetti’s interests in electronics is part of his entrepreneurial style. People either forget or overaccentuate how good a businessman Adriano was – sometimes he’s depicted as a shark, sometimes as a saint with his heads in the clouds. I think he had a clear, well-structured vision of how electronics would have changed the nature of the firm. So, when he started investing in electronics he was first and foremost aiming to grow Olivetti as a company. On the other hand, this plan intertwines with the very core of Olivetti’s ideology, which promoted technology and innovation as key factors in a vast campaign of social reforms. According to Adriano Olivetti, computers exist to serve mankind, to free humanity from ancient, hard labour – as he once said. So, in a few words, the promotion of electronics was part of an entrepreneurial plan – yes. But this plan could only have worked if rooted into a wider vision, involving the creation of an ideal, more human city, the so-called City of man”

The rules of this grand project were simple: industry exists to make a profit, but it can do something more. It can be an integral part of modern society and, as many other forces – like arts and literature – industry ought to improve everyone’s quality of life – that’s one of his goals. The world Olivetti envisioned was very different from the one he was living in – from the one we’re living in, even now, more than fifty years later. So, he was receptive to any kind of technological innovation that could foster his vision. That’s why he believed in electronics when most businessmen didn’t know a thing about it.

Back in the fifties, computer science was at his very dawn and no-one believed computers were going to have such an immense impact on everyday life. Nevertheless, Olivetti was convinced that electronics could become a powerful instrument to improve the human condition in general. But he didn’t just think about it. In 1956 the Olivetti’s Electronics Division was born. He entrusted the lab to one bright engineer, Mario Tchou – who had quite an international profile, particularly in the fifties, especially in Italy. Tchou was born and raised in Italy, being the son of a Chinese diplomat to the Holy See. He took his degree at Columbia University and was one of the most talented experts in electronics you could hire back in the days. Together with Adriano Olivetti, they build the team that created the Elea 9003, one of the first commercial transistor-based mainframes ever produced. It was a pride for the company, an achievement recognized by the President of Italy himself, who visited the lab and congratulated the team for their accomplishment. It was such a promising season for computer science in Italy. But it didn’t last for long.

The bell was already tolling for the Electronic’s Division. The first hit landed when Adriano Olivetti encountered a sudden death, killed by a stroke, in 1960. One year later, Mario Tchou died in a car accident. Over the years many rumors have circulated regarding the alleged involvement of CIA agents in these deaths. A more plausible explanation is that gray eminences intervened to undermine the Olivetti company using political means. De’ Liguori:

“It’s clear that the very existence of the electronics division caused some friction between Italy and the US. We know for certain that between 1952 and the national elections in 1958, Adriano Olivetti and his company have been spied by a CIA operative. It’s easy to guess why Olivetti was matter of concern for the USA. From a geopolitical point of view, Italy constantly wavered between siding with America and sympathizing with the Soviet Union. This is why, to America’s eyes Italy could not take the lead in such an important field as electronics, which, back then, had a profound impact on the arms industry, on war in general. Besides that, Adriano Olivetti was publicly promoting his own political, social and economical model – one model which appealed to the moderate countries from the eastern bloc. So, electronics should not be Italy’s business. And, as a matter of fact, the whole sector was shut down, packed and sent back to the US”.

More than fifty years later, it’s still difficult to measure how much the demise of the Olivetti Electronics division was some consequence of the political game played during the Cold War. However, it’s clear that, at least on a financial level, the Italian economic crisis struck hard on the company: Olivetti bonds plummeted from eleven thousand lire in 1962 to fifteen hundred lire in 1964. And sixty-four is the year when the so-called “rescue-team” took the wheel.

35% of Olivetti shares are now in the hands of a few Italian companies, amongst which are FIAT, Pirelli, Mediobanca and IRI, the Institute for Industrial Reconstruction, a public company whose job was to restructure private companies that were in bad shape after World War II. The vice-chairman of IRI is charged with the presidency of Olivetti, while a manager from FIAT is appointed CEO. Both the new president and the CEO refuse to further finance the Electronics Division because, as far as they see, Electronics is a risky venture Olivetti can’t afford. Mechanics, that’s a field Olivetti should focus on: it has been its core business for years – it will be its future, that’s what new CEO claims on the pages of Business’ Week.

To be fair, back in the sixties, almost no Italian entrepreneur would have considered electronics a sensible investments: managers simply ignored what this new field was about and, therefore, they weren’t able to foresee how lucrative it was going to become in a few years. That’s why Vittorio Valletta, chairman of FIAT, stated that Olivetti was in a good shape except for the Electronics division, a flaw that had to be eradicated.

And that’s what they did – in two steps. In the august of 1964, Olivetti creates a new company, the OGE – Olivetti General Electric. The name speaks volume: they partner with General Electric, the multinational conglomerate that is battling IBM for the control of the computer market. OGE absorbs the Electronics Division while Olivetti focuses on typewriters and mechanical calculators. Four years later, in 1968, Olivetti is no longer part of OGE: it sells its shares and leaves the electronics segment.

According to many analysts, Computer science in Italy has no future at this point: this is the end of the line. The leading company in electronics left all of its assets in the hands of an American firm. Apparently, the country cannot afford to compete in the computer rush, it hasn’t the resources, the means to finance research and organize mass production. And yet, someone does not agree. Against all odds, in the most hostile environment, a three men team will manage to devise and produce the first commercial personal computer, the Programma One-oh-One. They belong to the so-called Perotto team, named after the lead engineer, Pier Giorgio Perotto. Two teammates work by his side – Giovanni De Sandre and Gastone Garziera. Who are they?

Engineers and experts in electronics, the members of the Perotto team all worked in the Olivetti’s Electronics Division when it was left to General Electric. But how did the Perotto team managed to survive the reorganization and stick with Olivetti? Well, they avoided the transfer by making themselves unlikable. Back in ’64, when the division was to be absorbed by OGE, Giorgio Perotto hinted that something was wrong. He was right, even if at the time he couldn’t be aware of what awaited those who would be transferred to General Electric: a few years later, the American company would close the Italian electronics division, pack everything up and send it back to the US. Intuition? Sixth sense, perhaps? Anyway, Perotto did his best to convince the managers to leave his team out of the deal. He acted all uptight around the GE personnel, battling them over every small topic that came up during the meetings they had before finalizing the Division’s acquisition. Eventually, the whole Olivetti Electronics division was acquired by OGE, except for the Perotto team, which remained under Olivetti’s wing. This new situation was far from ideal, though.

Deals were done, promises of co-operation between the two companies were made but the reality was quite different. The Perotto team and the rest of the newly founded OGE Electronics Division shared the same lab, the same cafeteria, the same parking lot but they now belonged to two different companies – that didn’t want their industrial secrets to be revealed. It was like having a wall dividing the lab in two areas. And sometimes this wall was real because, for instance, the two teams were asked to enter and leave the building at different times. You never know what can slip out while casually chatting. This’s also the reason why Perotto took some photos portraying the team in front of the pieces they were working on. You can see these shots on our site – italianculturepodcast.com: you’ll notice how they all look a bit uncomfortable. They weren’t shooting those pics to have a nice souvenir: it’s evidence of their work, you know, just in case.

This situation was both a curse and a blessing. On one side, the company was completely focused on pushing the production of mechanical machines that, according to the high ranks, would have saved the company. This means that the Perotto team didn’t have a big budget and, more importantly, was perceived as a group of outcast by the main core of the company. On the other side, though, no one was keen to discover how they were spending their days: managers just weren’t interested in checking on them as long as they didn’t bother the company with strange requests. Only Roberto Olivetti, son of Adriano, tried to shield and encourage the work of the team, until the rest of the BOD managed to corner him and tie his hands. This gave the team the freedom to pursue its own agenda without any environmental restraints, except for the lack of resources and credit. Gastone Garziera was one of the last acquisitions of the Perotto team: he describes the bizarre position they were in:

“There were no inputs from above, management almost forgot we existed. Valletta said Olivetti should focus on mechanical products, so we were considered to be some kind of blight. Luckily, no one knew we were still active, or they would have shut our team down”.

This was the harsh environment that gave birth to the Programma One-oh-one.

In order to fully grasp the sense of what the Programma One-oh-one represented within the scope of computer science, it would be better to have a quick look at what was considered to be a computer back in the days. And glorious days they were indeed! The fourth of October 1957 a long cylinder made of metal and fire leaves the cosmodrome in Baikonur, piercing the atmosphere and delivering the first human satellite orbiting around the Earth. The Soviet Union has just launched the Sputnik One. One year later, the Explorer left Cape Canaveral, then Yuri Gagarin, then the Moon-landing. The space was certainly conquered by brave men and women, who put their lives at risk to push the boundaries of what is known a little further. But they weren’t reckless explorers who took a risk for the sake of it – not at all. Those missions required extremely careful planning and precise calculations, most of which were carried out by mysterious mainframe computers. Deep in the bowels of the research centers, these looming monsters pulsed, whirred and clanked, crunching numbers that put mankind in space, but that could have also destroyed us all. The earliest phases of the space rush coincided with the most delicate moments in the cold war. These same mainframes were asked to calculate the most convenient trajectory for a missile to obliterate the enemy before, or even after, being annihilated by the enemy’s bombs. So, these enigmatic machines were somehow perceived as responsible for the ever-looming war, some sort of Damocles’ sword hanging over our head.

Computers were also quite different from the ones we’re now accustomed to. Again, Gastone Garziera:

“For starters, mainframes were huge. It wasn’t like they could fit into a room, not at all. They were as big as one tennis court. And they also needed AC and to be completely isolated from the outside world. Only a few technicians were allowed inside the mainframe area, each one wearing lab coats. But before you could use a mainframe, you needed someone to have your problem translated into machine language. So, let’s say you are an accountant who has to calculate how much your company is gonna pay in taxes. First of all, you tell your problem to the analysts. These guys divide your problem into a series of steps that can be handled within the mainframe logical structure. Then, the analysts assign each phase of your problem to a different team of programmers. Programmers, in turn, are charged with translating the problem into machine language, thus creating your taxpayer program. But before you feed it to the mainframe, you have to make it “edible” and mainframes only eat punch cards. So, a trained typist has to write it down into a bunch of punch cards. Then it’s time to approach the computer. Almost time – because people took turns to use the mainframe. So you book a time slot, you hand the program to the tech guys and, when your turn came, they load it on the computer and eventually input the data. At this point, the computer often finds some kind of error, so you need to restart the whole process again, having someone look at your problem, etc, etc. Eventually, when everything worked out well, you would have your results printed by extremely loud printers that were installed in a distinct room because of their noise. The experience was completely different from the way it is now: the user never really used the computer, You just trusted the operators with your program and crossed your fingers. It could take a few months of work for a simple problem to be solved by different teams of people.”

Nowadays, computers have taken many forms: they’re everywhere. We wouldn’t be surprised to find one, sitting on a desktop at home, at the office or elsewhere. On the contrary, we would be shocked if we didn’t find one. That was not the case when, back in the days, computers were perceived as lab equipment. As we heard, those machines were out of reach for clerks, secretaries and, in general, for everyone who hadn’t a master degree in electronics. Even scientists couldn’t directly operate computers. Nevertheless, this variegated group of people was longing for a machine one could use on its own. Instead of wasting an entire day doing repetitive tasks, like calculating a mortgage rate or the force required to bend an iron bar – one could have trusted the computer to solve these problems and spent its time doing something more productive. Giovanni de Sandre is one of the fathers of the Programma One-oh-One. He claims the invention of the personal computer has almost been inevitable:

“Every accountant, every lab technician who worked in a small company, everyone who hadn’t access to mainframe computers but was still supposed to perform complex calculations, all these people needed a computer. Most of the people needed a computer but couldn’t and wouldn’t afford a mainframe. This problematic situation affected a lot of workers who truly wished to have it solved”.

There was a barrier between the machine and the commercial user – a wall the Perotto team would tear down by conceiving a revolutionary device. Again, Giovanni De Sandre:

“We were imagining a product with a few, core features. First of all, we wanted it to be user-friendly, so that anyone, even non-professional users could make use of it. Secondly, it had to be affordable, otherwise it would have missed the market segment it was meant to target. Finally, we didn’t want to make it huge – I mean – we didn’t want the machine to be as big as a cabinet. We wanted it to be compact enough to fit a desktop. This was also meant to keep the price reasonably low. These three guidelines helped us create the computer”

As the team gradually defined the concept, it became clear there was no machine like this and, therefore, no precedent could have led them in selecting the right internal components, or in designing the chassis. They had to create everything from scratch.

The building block of the Programma One-oh-one is the transistor. Invented in ’47 by Bell, the transistor is the beating heart of many modern appliances. This device was mass-produced using automated processes that achieved low per-transistor cost. Therefore it was a perfect fit for a machine, such as the Programma One-oh-one which had to be inexpensive, or at least cheaper than other computers.

What about the RAM, the piece of hardware where data and machine code currently used are stored? The Perotto team came up with a clever solution, using a delay line memory that, in brief, was just a circular steel wire in which the information is stored until it’s needed.

Keyboard and printer were inspired by the work of a soon-to-be-closed division of Olivetti, whose concepts the Perotto team salvaged. The inner structure of the computer was one of the trickiest parts: each hardware had to fit under the same, small hood, without risking anything in terms of functionality and ergonomics. And it wasn’t easy, you know: a modern microprocessor is small as a fingernail but back then, computers’ memories were big as kegs.

Speaking of memory, the team has to figure out where to store programs, those series of instructions that make the computer perform an action. While working on a prototype, the team discovered that every time someone shut down the Programma, programs went lost. This required the user to input the program again, and some of these programs were over one hundred symbols long. This was way tedious and, sometimes, even dangerous. De Sandre:

“So, we were at the lab, waiting for Mr. Galassi, the Olivetti’s head of sales. He scheduled a meeting to have a first look at the prototype, so we were there to show him the ins and outs of the machine. I remember that back then, the Programma was having a few issues, it got stuck now and then, and forced you to reboot it. The problem is, you see, we couldn’t risk a computer crash while Galassi was there. We were on the brink of a giant gaffe! To make the machine more stable you had to reset it, to bring it back to its original configuration. And so we did. Then we started to reinput the program we wanted to showcase, one command at a time. Knowing all this could take a while, we begin work early, so that we had enough time to complete the procedure before Galassi’s visit. But eventually, we hadn’t. We suddenly received a call from the reception desk: Galassi is early, he’s already there! While I went down to greet him, Garziera started inputting the program – thirty instructions to go. You can’t imagine how upset I was. Luckily, Garziera has the steadiest hand so he managed to load the program in time and everything went smoothly. Even more luckily, Perotto wasn’t there otherwise this conduct would have costed me dearly.”

To avoid further inconveniences, the team created a magnetic card where programs and data were stored: you just needed to slide the card in the Programma, wait a few seconds for the machine runs the program and then start computing. You can have a look at these peculiar ancestors of the floppy-disk on our site: italianculturepodcast.com. There, you’ll also find a video showing a test-drive of a functioning Programma One-oh-one. It seems an easy machine to operate and indeed it has been programmed that way.

Probably, the hardest part was inventing a new programming language. The complexity of the logical architecture controlling the computer was one of the reasons why mainframes were only used by trained technicians. And if you plan to design a new, more approachable machine, you’ll also need to conceive a programming language that anyone could understand and enrich. The team drew inspiration from the most intuitive solution available at the time – the calculators’ language. So, each key corresponded to one and only function. You could input sixteen different instructions: the four basic mathematical operations, plus square roots, plus a few instructions to print, transfer and automatically elaborate data.

In the fall of 1964 the Programma One-oh-One received its christening. Despite the tribulations, something new and unique has finally left the Olivetti’s lab. But again, its uniqueness was part of the problem because the time still needed to figure out how to prepare that unique piece to meet the market, that is – how to set up mass production.

In front of you, there’s a prototype. It’s sleek, well-polished in all of its parts; more importantly – it works fine, it seems to be a reliable machine. But it’s one, just one. And your company has recently dismantled every production line destined to assemble electronic machines. Any expert in the field has left, any top manager claims that the company risked bankruptcy due to the electronics division. And you have to sell your brand new computer to the company board. That’s gonna be a rough sales.

At first, the Olivetti’s management wasn’t excited by this peculiar machine, halfway between a calculator and a computer. In particular, they didn’t like the aesthetic: the prototype was functional but cumbersome. So, they proposed a design that, besides being quite nice, completely betrayed the idea behind the Programma One-Oh-One. According to the draft they proposed, the machine had to be heavier than the prototype, thus making it unmovable. Moreover, the ergonomics were thrown out of the window in favor of a more balanced design. The Perotto team sternly opposed this draft and called in Mario Bellini. This young, promising architect understood the concept behind the prototype and managed to draw the machine chassis without sacrificing beauty for user experience. That’s why the Programma One-oh-one has been exhibited at the MoMA and won Bellini a Golden Compass, the most revered industrial design award in Italy.

Nevertheless, this wasn’t enough to conquer the heart of Olivetti’s managers. Accountants said the whole Programma’s venture was dangerous because the profit margin was going to be too narrow. Customer care and plant managers were also concerned, for everyone who had training in electronics had already left the company and, therefore, no one was able to care of defective units. What about sales? Well, they claimed the Programma was a hybrid, something nobody wanted because there was no market for such a product. So, yes, it may seem absurd but, in a few words, they opposed the product because it was too innovative.

But, you know, innovative sounds good – this machine still could be of some use to the company, it says that we’re still running towards the future – that’s what managers thought when they decided to put the Programma on display at the Olivetti stand at the 1965 Business Equipment Manufacturers Association expo, that is the BEMA.

Her tutors didn’t really want her to shine but, with the help of a few trustworthy friends, she made it to the prince’s ball. And, despite everyone’s expectations, she became the queen of the dance. This plot summarizes both Cinderella’s tale and how the Programma fared at the New York BEMA. When the fair opened, the Programma was exhibited in a back-room of the Olivetti stand, someplace secluded and off-sight: the company wanted to showcase the calculators, the flagship products, which therefore occupied the front row. Fair’s visitors are a curious kind though and rapidly discovered where the Programma was hidden. So people started to flood the small room, thus forcing Olivetti to organize a security service focused on managing the crowd. “How much is it?” – “When will it hit the market?” – people couldn’t wait to bring a computer home. Someone was more skeptic, according to De Sandre’s recollection:

“You know, when we showcased the Programma, we found people inspecting the pedestal the machine sat on, looking for wires. They suspected the computer was connected to a bigger mainframe: they just can’t believe it could run programs”.

The Fair was an immense success in terms of PR: visitors placed several orders while newspapers started spreading the word: the NY Times, Business Week, The NY Herald Tribune – you name it – everyone was talking about the Programma One-Oh-One – the machine filling the gap between large conventional computer and the desk calculators. But what’s the feeling you get from using the first personal computer? What could you possibly do with a Programma One-oh-One?

If we look at the computer sitting on our desk today, we see a bunch of stuff: first, a keyboard with one hundred key and more, then a display, a trackpad, usb port, cd tray, webcam and microphone. The Programma One-oh-one is a modest sight in comparison: you can examine one of these machines by checking the photos we published on our site: italianculturepodcast.com. You’ll see a keyboard with just thirty-seven numerical keys, a green control light that tells whether the machine is on, a paper reel and the magnetic card slot. That’s it. A primitive interface, indeed: while today you can check in real-time the input you gave by looking at the display, this clearly wasn’t part of the Programma experience: you either gave the correct input or you found the error later, printed on the paper the machine constantly spat out.

You need to store a few files? Nothing easier: modern computers have hard-disk storage one terabyte large, that is One thousand billions of byte. The Programma’s magnetic card could save up to four-hundred-eighty byte. If you’re looking for an adventurous afternoon, you can transfer your one tera-worth files in the Programma magnetic cards: you’ll just need 2 billions of them. And a lot more than a spare afternoon.

Sometimes, though, you go for mobility rather than power. While most modern laptops weigh around half a kilogram, the Programma fitted a suitcase that, all considered, weighed thirty kilos. So, it wasn’t exactly a feather but it could still be moved around. The machine was indeed an immense step forward, since older computers weighed several tons and couldn’t be moved at all. One second, important area the Programma improved on is pricing. The cheaper IBM computer was sold for one hundred thousand dollars in 1968, which converts in over seven hundred thousand dollars today. In comparison to that, the Perotto team managed to design a rather inexpensive machine, priced over two million lire in ’68, which now would amount to twenty-three thousand dollars. It’s not something you would carelessly buy during a shopping spree at the mall, yet it’s something a small firm or a wealthy family could have purchased.

Now, you just unpacked your brand new Programma One-oh-One: it sits all shiny on your desk: what can you do with this machine? Again, not much in comparison to modern standards. You cannot write a paper on the Programma One-oh-one, you cannot watch a film or draw. Obviously, there’s no internet connection. There’re only a few programs, mostly calculation-related. But there’s a game you can play, some kind of craps the machine really like to win. We’ll talk more about that in the forthcoming Extra episode, to be released next Monday.

Nowadays, in order to launch a program or an app, you just need to tap on the screen or double click on the icon. The Programma’s programs, instead, were stored in small magnetic cards you slid in the machine and waited for them to be loaded: then, you could input the data. Then, the machine gave you an output. This was a convenient solution for the time, since it allowed anyone to use a computer without requiring a prior knowledge in programming. The Programma came with an array of pre-designed programs but it also allowed the user to write its owns, save them on a spare magnetic card and load them anytime he needed. And that’s revolutionary. All those people who had a knack for computer science were able to fully customize the use of the machine by crafting the programs they needed. This led the Programma One-oh-One to be the most versatile computers around, back then. This led the Programma One-oh-One to be the most versatile computers around, back then. For instance, we know of several applications that went way beyond the Perotto team’s expectations. Garziera:

“You could find any kind of programs. Before the Programma hit the American market, the company sent me to the US, where a team of twenty developers was writing software. It was meant to be sold with the machine at launch. Afterward, Olivetti published tomes full of instructions you copied on your spare cards to create new software: the book I checked contains nine chapters, each one presenting a few specialized programs. There’s software for electronic engineering, mechanical engineering, economics, statistics and more. Nine different disciplines – each one had its own load of programs”

So, you know the machine now, how it works, the ins and outs. Let’s get back to the story, let’s get back to the NY BEMA. The outcome was positive – we knew that – people and press welcomed the Programma with curiosity and true interest. The first orders started to come in: a growing number of people and firms asked for their slice of the future. And this was great for the team – you know – but also, a problem. When Olivetti struck a deal with General Electrics and created the OGE, all the electronic assembly lines were dismantled and all the people who knew a thing about electronics left Olivetti. So, how can you kickstart mass production in the span of a few months without having the equipment, the know-how and the full support of management? Here it comes another giant pickle for the Perotto team. At that point, the only solution consisted in taking advantage of one of Olivetti’s peculiarities: for years, the company promoted the growth of small, highly specialized teams, which served as a knowledge database and operative support for those who needed it. Let’s say you had a problem with conceiving a new printing device? You ask Giovanni from this or that division: he may have a prototype you can use on your machine. Perhaps you don’t know how to write this specific instruction in machine language? There’s a guy in the other lab who can teach you. Apparently, this same trick worked when the team was informally charged with organizing mass production of the Programma: they had to ask the right people. That’s what Perotto did.

In the span of a few hectic weeks, and thanks to the cooperation of a few plant managers, Perotto managed to convert an old production line and ready it to assemble the Programma One-oh-One. The workers took their positions and the machines came back to life: in a few, the first batch came out of the assembly line. The Programma was ready to hit the market. Probably. Because, you know, apparently no one down at the factory wanted to be held accountable for quality control. All in all, the workers didn’t know a thing about electronics, they weren’t able to tell if the Programmas were working or not. Plant managers simply said: “We assemble the machine according to your instructions – that’s it. If they come out flawed, it’s not on us. It’s on you.” You, meaning the Perotto team. Which was ready to go the extra mile. Garziera:

“One evening Perotto phoned us. It’s time, let’s do it now – he said. He borrowed the keys to the production site so that we could get in during the night. And so we did. The first batch was there, packed and ready to be shipped. We opened the crates, unboxed the Programmas and checked each and every unit. After we ascertained everything was in order, we packed the machines back and left. The computers were then shipped to America. Later we received a heart-warming letter from the States, saying that the Programmas were all right, perfectly working and ready to be sold”.

So, everything is set, the machines work and the first stock is bound to be shipped. But wait a moment: did Olivetti file the patent to sell the Programma in the USA? You cannot hit such a tumultuous market without taking bare minimum precautions. Moreover, according to the US Patent office rules, only a natural person could apply for a patent, so Olivetti, as a legal entity, didn’t have a chance to have his new machine recognized as company’s property. Unless Pier Giorgio Perotto applies for the patent and then sells it to Olivetti – which he did, for one single dollar. And, you know, that was a dollar well spent. A few years later, Hewlett and Packard copied a few parts of the Programma and put them into one of their products without paying due rights. Eventually, this came out publicly so that HP decided to settle and paid Olivetti nine hundred thousand dollars for patent infringement. Nine hundred thousand dollars in exchange for a one-dollar patent.

What about sales? How did the Programma fare in the open market? In 1966 two thousand pieces came out of the factory. Nine out of ten ended up on the American market, where they sold-out in the blink of an eye. As we know, HP bought one hundred units. NBC, the TV network, acquired five machines to keep track of some election results. Also, NASA had its share of Programma – forty-five to be exact. We know that because there are a few photos of NASA scientists working on a Programma One-Oh-One. You can see them on our site: italianculturepodcast.com. Apparently, they were quite eager to put their hands on the Programma. Garziera:

“These photos tell us something more. Nasa was such in a hurry to win the race to the moon, that managed to acquire a few pre-production units. Those Programmas weren’t meant to be sold, nonetheless, you can see them in the photos, sitting on the desks. I’m able to tell which one is a pre-production unit because the chassis is different from the one you find on regular units.”

Apparently, NASA scientists were fascinated by how easy it was for such a small device to handle very complex calculations – that kind of math that sent the man to the moon. But despite the initial success, the Programma One-oh-One never truly took off. What a missed opportunity.

The Perotto team won all the fights: first, they conceived something revolutionary. Then they built it. And they achieved all of this while working for a company that neither wanted the Programma nor had the instruments to get it done. They won all the fights but lost the war. Let me be very clear: the Programma sales were outstanding, nothing to say about that. The problem was elsewhere, the fish rots from the head down.

The company leaders were stuck in the fifties when mechanics were cutting edge technology in office appliances. Olivetti thrived with typewriters and mechanical calculators: why should they change strategy? – that’s what they thought. They didn’t see the world changing around them, they didn’t see the upcoming electronic revolution. The Programma One-Oh-One was a fortuitous bottom-up initiative that in 1965 put Olivetti ahead of every other company in the electronic business: they had something no one else had, they were leading innovators, they could have developed this line of production and make a fortune out of a venture like this. They did nothing. Of course, it’s easy to render such a harsh judgment in retrospect, but we cannot really claim they were just shortsighted. There are still a few elements telling us that the Olivetti’s management actually saw the opportunity but didn’t grasp it. After the Programma’s debut, the company inaugurated a modernizing process, aiming to ameliorate the efficiency in electronics production. They basically re-opened the Electronics division, hiring those who used to work in the old unit. But they were slow, too slow. Olivetti became a full-fledged Electronic company only in 1970, five years after the Programma was created. It was just too late: evolution in the electronic segment proceeds at a much faster pace. Not only Olivetti lost ground to its competitors, but it also fell behind in the race for supremacy in the sector. After five years of stagnancy, Olivetti wasn’t too far from where the Programma One-Oh-One venture left. Other, more reactive, companies had already reached and went beyond the point where the Programma was a novelty. Thanks to grand public funds, American firms were able to continually develop their researches and sell products to the richest client in the country, that is the US Administration in its many forms: the army, the IRS, security services – there’s always been plenty of agencies interested in machines capable of grinding big masses of data. Olivetti was running solitary, instead. Since the beginning of the Electronics Division, Adriano Olivetti tried to convince the Italian administration of the necessity to understand and embrace the forthcoming electronic revolution. He opened the company’s labs to students from public universities, he gifted the Ministry of Economy with a brand new Elea calculator. He received nothing in return. De’ Liguori:

“There’s not a shadow of doubt. The push for the development of the electronics industry in Italy and Europe, as it was endorsed by Olivetti, has been more or less willingly impaired by industrial policies, both on a national and international level. Besides that, one can argue that this process has been accelerated, even worsened by the business culture of the time, whose principles Olivetti never shared. This happened not only during the final stages – when the electronics division was dismantled, but even before, when Adriano Olivetti was still alive, when he was struggling to get the ED going”.

And so that’s how and why everyone forgot the story of the Olivetti’s Electronics Division; that’s why you’ve never heard of the Programma One-Oh-One, the first commercial Personal Computer ever created. Because victors certainly write history. But sometimes, those who lost are quick to forget too.

0 Comments