Images

- Pope Formosus

- Pope Stephen VI

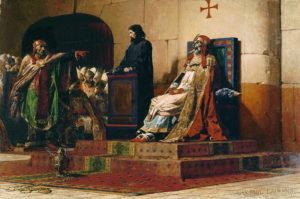

- Pope Formosus and Stephen VI by Jean Paul Laurens

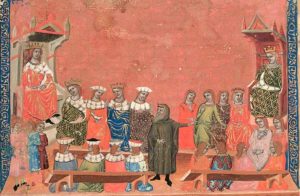

- Arnulf of Carinthia (first person on the left, sitting on the throne)

- Guy of Spoleto

- Lambert of Spoleto

- Interior of St. John Lateran

- Interior of St. John Lateran (between 1580 and 1625)

- Development of the Papal State

- Europe in 1000 AD

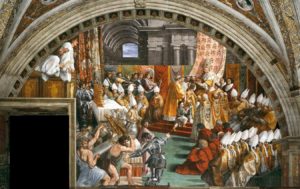

- Coronation of Charlemagne (800 AD)

Suggested Readings

- Roger Collins, Keepers of the Keys of Heaven: A History of the Papacy, Weidenfeld & Nicholson/Basic Books.

- Ludovico Gatto, Storia di Roma nel Medioevo, Newton & Compton.

- Jégou Laurent, « Compétition autour d’un cadavre. Le procès du pape Formose et ses enjeux (896-904) », Revue historique, 2015/3 (No 675), p. 499-524. URL : https://www.cairn.info/revue-revue-historique-2015-3-page-499.htm.

- Gaetano Moroni, Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica, Tipografia Emiliana.

- Claudio Rendina, I papi, Newton & Compton.

Music Credits

- Main Theme – Valerio Mirone

- Fearweaver – Three Chain Links

- Orc March Cello Trio – wolf sebastian

- The Garden and the Swing – Bisou de l’enfant sauvage

- Descension Oh Yeah – Nickleus

- Just Let Up – ROZKOL

- His Last Share of the Stars – Doctor Turtle

- Night III – Swelling

- Cobweb Morning – Kai Engel

- L’appel du vide – Nihilore

- The Swamp – Loyalty Freak Music

- Where was I ? – Lee Rosevere

- Octopussy – Juanitos

- Douce Dame Jolie – Tocs Occitans – Kyster

Sound Effects

- Ambient Battle Noise – pfranzen

- Big Reverb War Horn – newagesoup

- Creepy Dungeon Door Slam – Hybrid V

Transcript

What you’re hearing now, are the vesper bells of the basilica of St. John Lateran in Rome. The year is 897 and the sun is setting behind the hills. Inside the basilica, a young deacon approaches the Pope. He’s there to dress him with the papal garments. The pontiff stays still, seated on a chair, while the pallid priest comes closer. His hands tremble, his whole body shakes while he draws closer to the heir of Peter. He isn’t new to this, he has already helped the old pontiff to wear his robe, to put on his shoes, his soft leather gloves. So, why is he so upset? Why his fingers cannot grasp the buttons of the cassock? He holds his breath while looking away with horror. The fact is, you see, the Pope he’s helping is dead. Long dead. He left this world a few months earlier, during one of the most turbulent periods the city of Rome has ever experienced. And now, he’s back again – at least, his corpse is back – exhumed by the order of another Pope, who wants to literally drag him through the courts.

Pope vs. Pope, the living against the dead – there’s no precedent and (luckily) no subsequent case to a trial like this in the history of the Catholic Church. But how could this all have happened? And most importantly, why? Is this a sick joke? Perhaps it’s the work of a madman. The story is more complex than that. But, do not worry, this often happens when you unravel old facts. We’ll get to the bottom of this. Please, bear with me, this story comes from Ars Dicendi and today we’re dealing with Italian Culture.

We’re not accustomed to what happened during that chilly evening of 897. Our current mindset cannot accept the very idea behind what is called the “cadaver synod”. No one could really think of putting a dead person on trial. The reason is evident: that person is already beyond human justice. In jurisprudence, there’s something called “natural person”, that is a living human being – let’s stress living here – with certain rights and responsibilities under the law: once someone’s dead, it’s no more a natural person and, therefore, cannot be charged with anything. But what probably shocks us the most, is the subject and the promoter of this trial: they were both Popes. In modern times, the papacy is considered one of the most revered institutions. Popes – mostly seen as benign grandfathers – embodies the voice of compassion. But clearly, that wasn’t always the case.

Saeculum obscurum – the dark age – that’s the name historians gave to the period in the history of the papacy that spans the tenth century. To be conservative, it was a wild age. Pope succeeded Pope with disturbing rapidity: 24 Popes in ninety-four years. One-third of these 24 Popes were assassinated. Five were just murdered or imprisoned and then killed. One died by the consequences of severe torture, while another was killed by his own escort: they tried to poison him but, as the venom wasn’t acting quickly enough, they opted for smashing his head with a hammer. There’s plenty of morbid stories that reflect the decadence of those years but we aren’t going to deal with them right now.

Now, it’s time to come back to st. John Lateran and focus on the cadaver trial, the event that paved the way for the dark age of papacy. If you’re looking for a more immersive experience, check out our site – italianculturepodcast.com. You’ll find plenty of photos and paintings that may help you visualize the places, the actions and the actors in this trial.

We left the young deacon dressing the Pope’s corpse, just before the trial. The dead pontiff was once known as Formosus – which means good-looking in Latin. He’s not good-looking anymore, rest assured, but besides the state of his body, his whole figure still instills reverence in those who look at him. He wears the regalia he once wore when he was alive, like the heavy metal crown that makes his head tilt on a side. Around him, a full team of bishops play as witnesses and co-accusers: spread in two long wings, they approach the throne while the trembling deacon tries to arrange Formosus’ stiff body into the most uncomfortable seat. Stephen the fifth leads the prosecution: he is the incumbent pope, the most energetic promoter of this trial. He looks splendid and terrible in his luxurious attires, while he raises the voice numbering a long list of sins and felonies Formosus allegedly committed during his tenure. We don’t know exactly which words Stephen pronounced in his closing argument, but historians were able to reconstruct the gist of it.

The Lateran basilica is now silent. The prosecution waits for a response, for a defense that can never come. But it comes, in the end, it comes as a feeble voice from behind the throne where Formosus sits. It’s the young deacon, who musters all his courage and speaks, or at least tries to speak, in defense of the dead Pope. But despite his efforts, there’s only one possible outcome. The trial is a farce and as a cruel farce, it ends. Stephen announces the punishment: Formosus, his deeds, his memory will be forever damned. His regalia are torn off and shredded in pieces while the guards cut off his fingers of consecration. Then, a mob drags his body along the streets of Rome until they reach the Tiber: the river finally embraces Formosus while the people of Rome come back to their homes in the shadow of Saint Peter’s Basilica.

What do we see today, when we look at the papacy? We notice the pump, the luxe but, mostly, we recognize that some sort of aura permeates the figure of the pontiff. He teaches what’s good and what’s evil according to the Catholic catechism, he explains why good Christians should behave in a certain manner, refraining from some activities, while indulging into others. That’s how the Pope exercises what is called “spiritual power”. But there’s also another kind of power that Popes held for centuries, that is the temporal power, their power over the reign of men.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the Popes claimed the role of the pontiff, once owned by the Emperors. They became leaders of the church and princes of Rome, where the seat of Saint Peter survived while kingdoms rose and fell. So, during the middle ages, Popes were like kings; they ruled over their own state, the pontiff state, that occupied a large part of central Italy. In addition to that, they were recognized as the only earthly power that could bestow the crown of Emperor or King. As such, they were involved in complex political schemes – trying to defend their power, both spiritual and temporal.

The Pope had to play his role of first among equals in a harsh environment, trying to keep his allies close but not too close. The last protector of the papacy had been Charlemagne, ruler of the Holy Roman Empire, herald of Christianity and leader of the Christendom. His rule ended in the winter of 814.

Charlemagne divided his realm amongst his sons – who went to war one against the other, shortly after the father died. For more than fifty years brother battled brother and uncle fought nephew. Eventually, the once monolithic empire crumbled into many small states, controlled by local powers who enforced their law upon the land. By the end of the ninth century, when the trial happened, the European political landscape was dominated by national rivalries and local contentions alike. That was the time when the characters of our story emerged from the ever-flowing course of history.

The first actor in our story is Arnulf of Carinthia. He overthrew his uncle, Charles the Fat, and became king of East Francia. Despite its name, the Kingdom of the East Franks, has nothing to do with modern France and, in fact, its territory occupied a vast region corresponding to modern West Germany. To get a clearer view of the situation, visit our site – italianculturepodcast.com – and look at the historical maps we published: it may help you visualize the places and the players in our story.

So, who was Arnulf? He’s remembered as a warrior, a cunning general who learned the art of war by keeping at bay the Viking raiders in the North. His armies were vast, his soldiers well trained: under Arnulf’s rule, West Francia became the military power of that time. And, as history teaches us, military powers often expand at the expenses of nearby kingdoms. So, Arnulf was eager to jump into the fight to claim the Kingdom of Italy. Only one man stood between him and the Crown: Guy of Spoleto, who was the second major contender for the throne and, also, the second character in our story.

To be more precise, the whole Spoleto family played a pivotal role in the events that led to the Cadaver trial. Guy, his wife Ageltrude, his son Lambert – they all had two items on the agenda. First, to expand the Duchy of Spoleto. Second, to raise their status amongst the European aristocracy. That’s why Guy initially aimed at the Crown of West Francia. Unfortunately for him, the other contender had better cards and eventually ascended the throne. So he came back to Spoleto, beaten but not defeated: he then shifted his attention to the Crown of Italy. This may seem a fallback if we consider the two kingdoms with regard to lands and raw power. However, Guy was also after the prestige, something one cannot measure in terms of acres and coins. The crown of Italy had been historically linked to the Emperor’s title and, therefore, the ruler of Italy was also considered to be the head of the Empire. That’s how and why the Spoleto family ended up crossing swords with Arnulf.

Both Arnulf and Guy of Spoleto had Carolingian blood, both had the right to claim the crown of Italy, and both eventually did! First, it was Guy’s turn. He was able to forge an alliance with the Pope of the time. The pact between crosier and sword bore fruit: in 888, Guy was proclaimed king of Italy in a diet in Pavia. One year later, he was formally crowned Emperor by the Pope. And then, the balance changed. The Pope died and Formosus ascended the throne of Saint Peter.

Formosus is the third and last character in our story. In the beginning, he was the bishop of Porto, a small town near Rome. Then he was elected Pope. As we saw, being the Pope in the ninth century had a lot to do with political games. And, back then, anyone involved in politics had to answer one question: who should be the Emperor? Should he come from Germany? Or should he speak French? According to Formosus, the emperor had to be one prominent figure of the German party. And this was a problem for him because Arnulf, the big player in the German faction, was far away from Rome most of the time. Formosus was alone: no-one could protect him, no-one could defend the papal state from the Spoletos. Formosus had a few options at this point. He stalled the Spoletos, trying to keep them at bay: in 893 he accepted to crown Guy as emperor while his son, Lambert, was recognized as co-emperor. In the meantime, Formosus tried his best to summon Arnulf and his army, sending secret letters and diplomatic missions up north. The German King needed the tiniest excuse for trying to seize the Italian crown: so here he comes in the year 893. His troops cross the Alps and march towards Milan and Pavia. Both cities immediately fall, acclaiming Arnulf as the true and only power in the peninsula. Satisfied, Arnulf decides to stop his descent upon Rome. He doesn’t need to – he has already sent the message. So, the German King chooses not to engage Guy’s army, and he probably makes the right call because, a few months later, Guy of Spoleto dies by stroke. Formosus seizes the day: it’s the perfect time to get rid of the Spoleto family once and for all. He summons Arnulf again: in his letter, he asks him to hunt down all the bad Christians who endangers the Holy See.

Somehow, the Spoletos get word of Formosus’ double-dealing and take the initiative. Ageletrude, the widow of Guy and mother of Lambert, rushes to Rome at the head of the Spoletos’ army, seizes the city and arrests Formosus. The Pope is now held captive in Castel sant’Angelo, his own fortress. Arnulf’s response comes quickly: he rallies his troops and once again crosses the Alps. This time, though, he runs all the way to Rome, unstopped and unstoppable, besieges the gates of the Eternal City, breaks in and routs the Spoleto army. The pope is free again.

Formosus sees his liberation as the chance to tighten the relationship with the German King who, in turn, expects to be duly repaid for his loyalty to the papacy. Rome is still in turmoil but there’s something far more urgent.

The ceremony follows a solemn protocol. In some way, it reflects the dynamics of power between pope and king. Arnulf awaits for Formosus on the stairs to st. Peter. The Pope reaches the king and tributes him great honors. Then the gates of the basilica open and both men enter. While pacing towards the altar, Arnulf savors his victory: he’s going to be crowned by the pope, the only true coronation. And that’s exactly what happens: Arnulf is proclaimed Emperor and protector of the Papacy.

The Romans acclaim the new emperor while Arnulf’s enemies fall victims of his wrath. He organizes a series of tribunals that persecute who belongs to the Spoleto faction. Trials and public executions become part of the festivities. The streets run red with blood and wine. After fifteen days, the German emperor leaves the city. He’s ready to close the match, his army points towards Spoleto, the town that gives the name to the enemy family. Ageltrude and Lambert barricades themselves in, waiting and hoping for a swift death. // On the road to Spoleto, Arnulf’s army has stopped: the Emperor is ill, someone says, he cannot move. The army surgeon examines him and the response is final: paralysis. Arnulf, the fierce warrior-Emperor, would never leave his litter again. It’s time to retreat, it’s time to come back to Germany. The Spoleto family is spared.

As you might expect, Formosus finds himself to be in a very bad spot. His protector, immobilized, is retreating. His enemies, alive and furious, are regrouping just outside the borders of the papal state. What would you do, at this point? Formosus never had the chance to make a move because he died the fourth of April 896. Maybe it was a natural death, maybe he was poisoned, we don’t know that. We only know that his ordeal has just started.

That’s the background story, that’s how Formosus walked to his grave. Now, it’s time to investigate why they made him leave his tomb, why such a ghastly trial tainted the sacred halls of st. John Lateran.

Let’s slow down and analyze the situation. What’s the most absurd element in the trial? The corpse, of course. But is the presence of the corpse that absurd? On one hand, there have been several posthumous trials in the middle-ages. One of them even involved a Pope, Honorious the first, who was struck by an anathema several years after his death. Honorius was luckier than Formosus, though, because his accusers didn’t summon his corpse. They just condemned him and left him be. On the other hand, exhuming a corpse to put it on trial wasn’t as rare as we think. Even if this seems completely unthinkable according to modern standards, the medieval legal practice allowed to put corpses, even skeletons on trial. Actually, it was considered rather normal to exhume political enemies during popular uprisings to hold them responsible for their past wrongdoings.

Given this broader context, we should look at the trial from a historical standpoint. We know that it wasn’t like day-to-day business for the papal court to put a dead Pope on trial. We have proof of that because a few years later another papal synod reprimanded both organizers and participants in the trial to the point of burning all the proceedings. Nevertheless, we ought to recognize that the Cadaver trial was at least something thinkable within the cultural coordinates of that time.

This said, we still ignore why the trial actually happened. What pushed Pope Stephen to dig one of his predecessors out of the grave? Why did he make Formosus’ corpse face trial?

Madness. Madness is the first thing that comes to mind when one tries to explain how such a trial happened. And madness is actually the rationale historians from the Middle Ages used to explain Stephen’s behavior. He must have been mad, he hated Formosus beyond reason. Many people believe that if something seems too abnormal, it has to be placed outside the domain of reason. But that’s a very simple explanation. Even too simple. For instance, one may ask: granted that Stephen was mad, why did he hate Formosus so much?

This leads us to investigate Pope Stephen’s background, to uncover his allegiances. It’s very likely that he looked at the Spoleto family with benevolence. After Arnulf’s quick retreat, Ageletrude and Lambert of Spoleto represented the most powerful players in central Italy. So, it’s possible that Stephen felt the urgency to forge an alliance with them. Perhaps he feared some sort of retaliation. Perhaps he was voluntarily in league with them. It’s difficult to tell. We know, though, that he later recognized Lambert as the only Emperor, thus dismissing Arnulf’s claim to the crown. Anyway, if Stephen was indeed allied with Ageltrude and Lambert, the Cadaver trial is by large the meanest revenge one can get over a dead enemy. From the Spoleto family standpoint, Formosus was the villain: first, he crowned Guy and Lambert while secretly siding with Arnulf. Then, he summoned the German king not once, but twice. Finally, he unleashed a wrecking ball army upon the family, nearly wiping them out of their hometown. They probably had hard feelings towards Formosus, that’s obvious. Truth be told, though, politics is rarely a matter of feelings. Especially during turbulent times, politicians need to carefully measure how to blow the strike, trying to maximize the effects, while minimizing the negative reactions. And if you think through, the Cadaver trial had a few consequences that actually harmed the family. When Formosus was condemned, all his acts became null. This means that every coronation he celebrated was now voided and, therefore, even Lambert’s investiture was considered to be invalid. And that’s something the Spoleto family did not want. Because, just like nowadays, politics in the Middle Ages were focused on the legitimation of power. Just think about those formidable kings who came down to Rome to have an old guy put some fancy metal disk over their temples. Did they need that from a practical point of view? They, who had armies, who ruled over many lands and amassed richness beyond measure? These coronations didn’t gift them with more soldiers, castles, territories. That old man clothed in white gave them something better, the best instrument a ruler can get: he gave them authority, an undying, unyielding consecration that came directly from God in heaven. When the Pope performed the coronation, these lords gained the respect of their servants, the impalpable right to rule over their lands.

Power speaks his own language. It flows through symbols and condenses itself in forms and images. When you touch those symbols, you reach the immaterial power beyond them: that’s how concrete actions influence the intangible reign of politics. That’s the path Stephen traveled when he decided to put Formosus on trial.

To decode Stephen’s intention we’ll look at the language the trial spoke – the symbols it played with. We know Formosus was dressed in his old regalia. How the violent exhumation of a body complies with the gentle action of dressing that same corpse in elegant attire? Why this care? Why Stephen treated Formosus’ corpse with all the dignity a pontiff deserves? And why such caring manners did not extend beyond the time of the trial, neither before nor after? It was brutality in disguise: for this trial to work, Formosus had to be recognizable as a Pope, he must wear all those garments that made him a Pope when he walked the earth. Stephen aimed to destroy Formosus not just as a man, but as a symbol.

It is evident now, that something more than a dead pontiff is undergoing a trial. The very papacy of Formosus is under siege. As we saw, Stephen attacked Formosus’ papacy by hitting its symbols of power, like the fingers or the regalia. So, as the sentence was pronounced, Formosus was no longer a Pope, actually – he had never been. Stephen literally expunged Formosus from st. Peter’s heirs by removing his corpse from the place where Popes were traditionally buried and throwing it into the river.

The trial was a drastic measure and it cannot be reduced to the simple act of smearing Formosus’ image and memory. It shows how the political landscape extends beyond the mere present. Those who want to play a part in it, have to reposition themselves by dealing with what happened and what’s likely to happen. If this was true then, it still is nowadays.

Our understanding of current events is determined by the sheer amount of information we can find on modern media, be it false or true reports. The same cannot be said of our comprehension of a trial that transpired over one millennium ago. Reliable sources are scarce, to say the least. The remaining recollections of the event come from later commentators, sometimes hostile to the factions in play, sometimes just too far from the action to develop a well-rounded opinion. To us, then, the story of the trial is like a placid lake. We see a bubble, here and there, we notice a ripple. We know that something is going on under the surface, but we can only grasp a fraction of it. To get a grip on this situation, we shall approach the problem from a different perspective. Instead of asking why did Stephen erase the papacy of Formosus, we will investigate what he gained and what he lost from acting so.

In the world of politics, relationships define the map of power. Politicians cultivate connections in order to build a structure where other powers recognize them as a force, a political one. That structure gives them authority. If connections are cut, then the structure falls and authority suffers a critical stroke: this means losing allies and, perhaps, gaining new enemies.

By voiding all the ordinations celebrated by Formosus, Stephen erased those connections his predecessor had built in his lifetime. Anyone who was in debt with him saw his bill paid. Anyone who gained power by joining Formosus lost his position in the Christian world. Any bishop he ordained, any Lord he helped – all of them suffered the consequences of the Cadaver trial.

The score is set back to zero. Even for Stephen.Yes, Pope Stephen.

According to canon law, one cannot be bishop of two cities. This is an old rule the Vatican adopted to keep the bishops under control: by ruling over two or more dioceses at the same time, a man concentrated too much power in his hands.

Stephen invoked this old rule to contest Formosus’ authority. As we have seen, Formosus had been ordained bishop of Porto first; then he was elected pope, that is considered to be the bishop of Rome. So, two times a bishop. Hence the accusation, the trial and so on.

Now, you wanna know the sketchy detail here? Stephen stripped Formosus of his papal dignities because Formosus was twice a bishop while he, Stephen, was twice a bishop himself. How did this all work out? Well, Stephen had a trick up his sleeves, of course. You see, when he was young and Formosus was still the incumbent pope, Stephen was ordained bishop of Anagni by Formosus. Now, he needed to get rid of that consecration to be just bishop of Rome, or Pope, otherwise, he would have infringed the same canon law he invoked against Formosus, right? So, he voided each and every Formosus’ ordinations, and this includes his consecration as bishop of Anagni. So Stephen wasn’t bishop of Anagni anymore and, therefore, could now be bishop of Rome, also known as – the Pope. Thanks to this masterly move, Stephen both discredited Formosus’ papacy and legitimized his own role as the new leader of the Church. It seems at least possible that, due to the trial, Stephen was able to validate his authority, maintain and consolidate power. And to that end, he used all the instruments he could gather. He made up a rite of exhumation that is the exact opposite of the ritual bury reserved to Popes and saints. He found cultural legitimation of the exhumation in the works of Gregory the Great. He gained more credibility by playing by the legal rules of that time: that’s why he summoned a full council. He found security in numbers because the many bishops participated in the synod, the more his authority grew. To that end, he also shook hands with noblemen and plebeians alike, he involved them in the trial by entrusting the corpse mutilation to them, after the trial ended. Clergy, aristocracy, plebeians; the authority granted by canon law and the validation offered by doctrinal reasons. Stephen had it all, for a moment, a brief, flickering instant. He ended up learning what he proved us, that power is as volatile as the alliance that secures it. The trial and its consequences must have displeased someone. Someone unknown. Someone powerful.

A few months after the Synod, in the August of 897, Stephen was deposed and dragged in chains to Castel Sant’Angelo. There he died, strangled.

0 Comments